Many successful sportsmen have struggled with their personal lives at the end of their sporting careers. Who can forget the images of a washed out Paul Gascoigne, overweight and dependent on alcohol, struggling with his demons as he tried to make some sense of his life after a glittering, but not entirely fulfilled, career as a footballer? Of course the cycling world is no different: Marco Pantani suffered a terrible decline into drug addiction that tragically destroyed him. Even the apparently unshakeable Eddy Merckx floundered after retirement for a while, as he sought out a life in business as a prefabricated building salesman before being persuaded to go into the bike building business!

Maurice found love and happiness after racing with his wife Mia and De Ver Cycles

Last week we profiled the early life of Maurice Burton as a track racer. Maurice had forged a career for himself on one of the toughest circuits in the world: the Six Day Races. Running between September and February, the Six Day Races would attract crowds of up to 10,000 people a night. Starting as a complete unknown in Ghent, the heart of Belgian track racing, he became a fixture on the scene and one of the most sought after riders in Europe and beyond. He was on the cusp of greatness as he reached the peak of his physical fitness, racing with acumen and toughness. Then came a horrific crash in Buenos Aires where his leg was smashed up and had to be reconstructed with pieces of metal, putting an end to a successful career and the possibility of an even more stellar future.

If it wasn’t for that crash, who knows what he could have gone on to achieve? But Maurice’s story of how he was able to forge a life for himself beyond the world of track racing, encapsulates the same bloody mindedness that brought him success as a professional cyclist.

Maurice shakes his head and looks back on those dark days. “I was still a young man, you know?” At least he had enough money in the bank to tide him over a little, while he considered his future. He returned to London after a 10 year stint in Belgium. “I didn’t do anything for about two years.” But the money he’d saved was always going to run out eventually and the day came when he realised he had to get a job like everyone else. “I couldn’t even get a job as a mechanic at Evans! I lived the life, but before you know it, money disappears.” Maurice’s injuries meant that his racing days were over but he could still ride a bike, so he went back to what he knew best. He found himself working as a cycle courier in London.

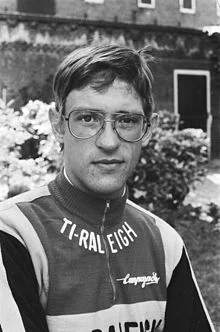

Gerrie Knetemann image courtesy of Wikipedia

One day, when he was out delivering a package in the West End of London, he was nearly taken out by a taxi door being swung open into his path. And there was the Dutch road cyclist, and former World Champion, Gerrie Knetemann. Maurice made out he was just out on his bike rather than working as a humble courier and it was this moment that dragged him back, forcing him to follow a path more befitting of a former National Champion.

He was still in touch with Peter Versleydonck, an old friend from his track racing days back in Belgium. Peter owned a bike shop in Streatham and was keen to move back to his home in Australia after getting involved in an awkward relationship with a neighbouring business! He persuaded Maurice to buy the shop off him and since that day in 1987, De Ver has gone from strength to strength, expanding to three times its former size while Maurice has also developed a unique friendship and partnership with Ernesto Colnago himself.

That success hasn’t come easily. Bike retailing is a tough business, even more so in the days before British Olympic medals and three British winners of the Tour de France got a whole nation back on their bikes. But as Maurice says, “Once I make up my mind, I will do it. I will find a way to do it. It’s tough, but it’s nowhere near as tough as riding a bike for a living!”

With the same determination that brought him success on the track despite not fitting in with the blazers of the white middle class British Cycling Federation, Maurice set about building a new life and a new business that continues to thrive to this day. “You reach a point when turning 30 when you can’t afford to make mistakes any more. I suffered a broken leg when I was 28 years old – I had a lot of time ahead of me. I knew that I could’ve carried on, but that’s life. I still enjoy riding my bike – that’s the main thing.”

And Maurice is happy to admit that he will go about fixing more personal aspects of his life with same single-minded approach. He recalls how he was unhappy with his relationship with his then Jamaican girlfriend. He decided to call an end to it after getting a hernia lifting his tandem into the coach after struggling to drag her up Ditchling Beacon. “I felt something go and it wasn’t good. It was a hernia!”

Maurice found his future wife Mia through a Philippine dating agency

“I thought to myself at that point, you know, what’s going to happen to me down the line, I need to sort my life out a little bit. What happened is, I used to go to Tesco. There was a Jamaican security guard in there and we were talking one day and he was telling me how he got married to this Filipino lady and I started to think about these things. I thought, it sounds good to me, it sounds like a good idea! So I thought, I think I’m going to give that a go. What I did, I went down to this Philippine friendship club. You paid £35 and you could choose from a box of 10 index cards of people to write to. She was one of them!” Mia interrupted to point out that she’d been number 11 and that Maurice had convinced the club to let him take 11 cards rather than the 10 he’d paid for! “I wrote to these women, some replied and some didn’t, and then this one, Mia, yeh, was in her toga in the picture, she was a nurse by profession, I thought that’s handy after the hernia! I just decided, you know and I did it and that was it and I went over there to the Philippines, we were writing for a few months, we met in the February and by the end of March we were married. That was 24 years in March now. I’m very much like that, you know, I just make up my mind and that’s it. I don’t take long to think about things, to make decisions. If I’m going to do it, I’m going to do it and that’s it. That’s the truth of it, that’s what I did.”

In 2008, Maurice Burton was hit by a car while out riding in Lanzarote. He was knocked unconscious for 15 minutes after flying 2m in the air and smashing into the windscreen. His riding partner, who was also a doctor, thought he was dead. By some stroke of fate, or luck, he was still alive, but he’d broken his back. His physical strength helped pull him through, the same physical strength that sustained him as a professional racer.

Germain Burton - following in his father's tracks

Maurice’s elder son, Germain, 21, named after Maurice’s Belgian mechanic and friend, also has that innate physical strength – he’s forging a career as a track cyclist himself and is part of the British Cycling set-up, coming first in the British National Team Pursuit Championships last year and taking third in the UCI Track Cycling World Cup. Maurice takes us to meet his sprightly 96-year old father after our chat, the progenitor of this line of freakishly strong and talented riders. And you can see that strength through all three generations.

Maurice with his 96 year old father

But I can’t help but think back to Maurice’s comment at the beginning of our conversation about the need to be strong, not just physically, but to have that sheer bloody mindedness and force of personality, the will to “force your heart and nerve and sinew” that beats your rival’s wheel. As he says, “Once I make up my mind, I will do it. I will find a way to do it. Like getting that bike from that front garden in Forest Hill, really.”