By Robbie Broughton

As Chris Froome secured his fifth Grand Tour victory yesterday, and only the third man in cycling history to achieve the Tour/Vuelta double in the same year, he could be forgiven for looking on enviously at his rival, Alberto Contador. The Spaniard riding his last race may not have even made the podium but the Spanish public’s love and adoration for him could not be denied.

(Photo courtesy of Team Sky)

It seems that whatever Froome manages to do, and his success to date has been astounding even compared to cycling greats like Merckx, Hinault and Anquetil, the British press and public remain underwhelmed. What should have been front page news was relegated to today’s Sports pages, and even then, was deemed by many editors to fall below the importance of the news that Crystal Palace have sacked their manager.

It can seem confusing when you consider the high profile that cycling has begun to enjoy in recent years. Bradley Wiggins, Chris Hoy and even Dave Brailsford have all been knighted. Publishers eagerly fork out commissions for cyclist’s biographies and cycling races are broadcast on Eurosport, ITV4 and the Bike channel.

Our appetite for reading about and watching cycling is greater than it has ever been, yet Britain’s most successful road cyclist of all time remains unloved and struggles to make the long list of Sports Personality of The Year.

Froome at this year's Tour de france

It doesn’t help that, as has been pointed out many a time, Froome was born a Kenyan, brought up in South Africa and only changed his nationality to further his career.

While Froome is not the first foreign sportsman to claim British nationality, he has been less accepted by many other stars who have claimed British ancestry for their own convenience.

Kevin Pietersen, another South African, even won our hearts for a time while he was playing well and not undermining his teammates. Canadian Greg Rusedski could never quite compete with Tim Henman in the popularity stakes, despite greater success on the court, but he was at least grudgingly accepted. Tony Greig, whose South African vowels were more reminiscent of the high veld than the South Downs, was feted as captain of the British cricket team. Meanwhile several of our present crop of English rugby players have stronger links to the Pacific islands than our own temperate shores.

The difference between these examples and Britain’s most successful cyclist of all time is that, while the Vunipola brothers ply their trade on the muddy rugby pitches of this green and pleasant land, Rusedski waved a Union Jack at the Davis Cup and Greig scored centuries at the Sussex county ground in Hove, Froome rarely visits his adopted country.

He lives in tax-free Monaco and trains wherever the gradients are steep enough and the altitude is high enough. And so it’s the hairpins of Tenerife, the French Alps and Mallorca that are more familiar to him than the rain sodden lanes and grey high streets that have just hosted the Tour of Britain.

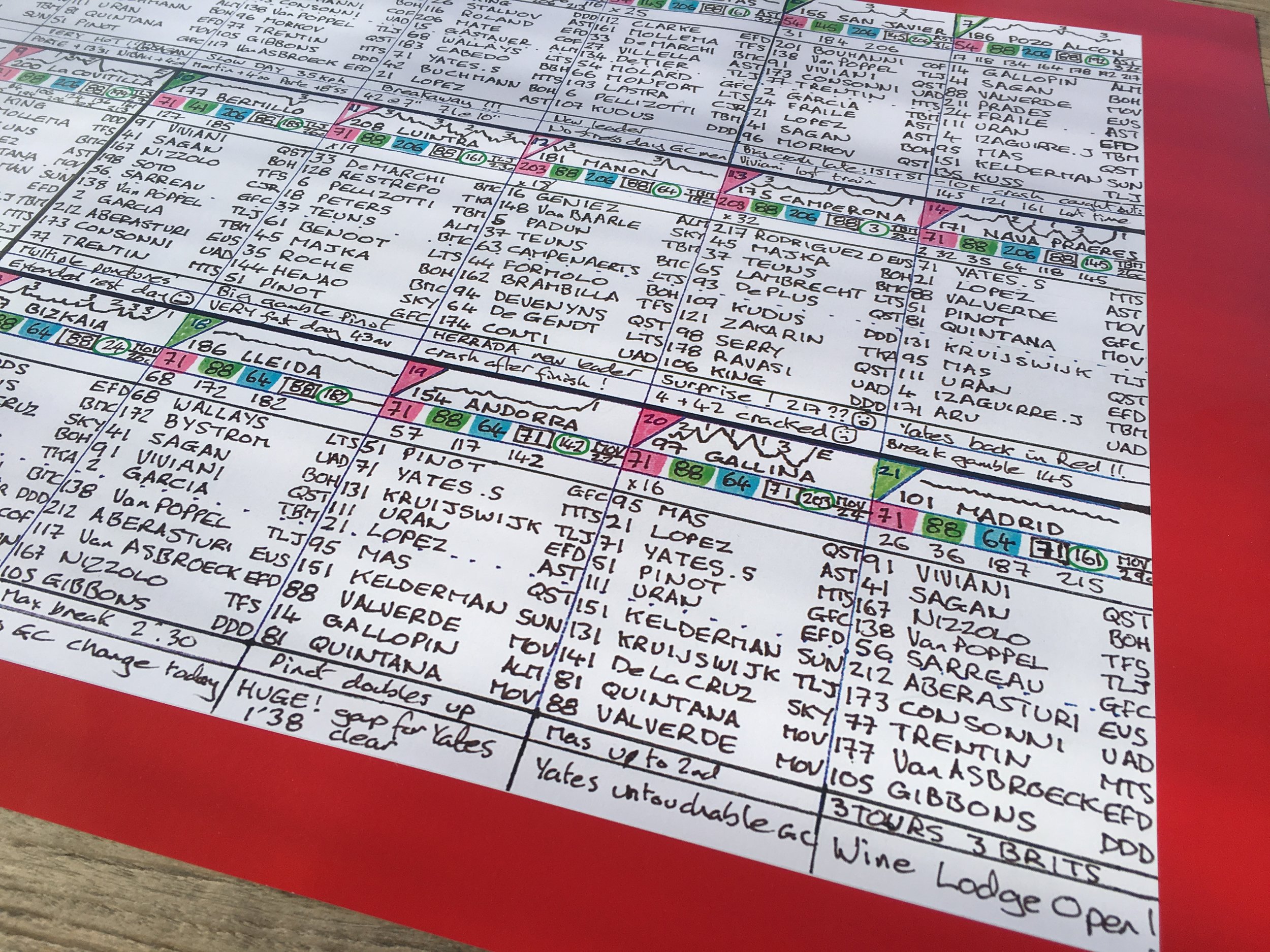

The legs of a five time grand tour winner

Froome has encountered criticism from the cycling cognoscenti since his meteoric rise in the Vuelta back in 2011, when he leapfrogged Bradley Wiggins, his team leader at Team Sky, to take second place in that year's tour. There have been questions about his remarkable improvement as a cyclist (explained by him overcoming Billharzia), his gangly and inelegant style and his descending abilities.

His tenuous loyalty to cycling’s darling, Bradley Wiggins became a headache for Team Sky in the 2012 Tour and many die hard British cycling fans turned against him then. Meanwhile his robotic style distanced him from others. He always seemed to be reliant on reading his power meter and his post race interviews have all the passion and excitement of a civil servant’s briefing for a government minister.

Despite his impeccable good manners, his modesty, his continued gratitude to his team and his respect for his rivals after pulling on the yellow or red leader’s jersey, his comments seem to trip too easily off the tongue for some. Perhaps there’s just a sneaking suspicion that, while Chris Hoy may genuinely have felt the bland utterances that spilled from his mouth, Chris Froome maybe doesn’t.

(Photo courtesy of George Deswijzen)

And yet…and yet…just look at what he’s managed to do! Despite his ugly sticky out elbow style and bobbing head, he’s become, not only the best climber in the peloton, but the best time trialist too, that discipline where it has always been deemed that one needed the grace and rock steady poise of Anquetil. Decried as a clumsy descender, he’s now one of the best in the peloton at flying down a mountain at 70 kmh. Branded as a conservative racer, who can forget the guts he showed to win on Ventoux in 2013?

And he wins. He has shown, time and again, that he has the canny racing acumen of the best. It’s not for nothing that he’s been described as having the face of a choirboy and the mind of an assassin. Surrounded by the strongest team he may be, but who else can muster his troops, deploy them like weapons of mass destruction and expect their unfailing loyalty? Not many in the peloton have been able to do so. Britain had its first grand tour win in 2012. Since then Froome has won five. FIVE!

And isn’t it, in fact, a good thing that we have a clean rider and one that can present a respectable image for a tarnished sport? What other sportsmen have the grace (or ability) to deliver a victory speech in French or Spanish as well as English? And it may be boring that he’s so polite and well briefed by his PR team, but isn’t it at least, refreshing, to hear someone speak with intelligence, dignity and modesty?

There may come a time when Tours of France and Spain aren’t so readily won by a Briton. Perhaps it’ll only be then that we open our arms to Chris Froome and finally declare him as our greatest cyclist of all time.