By Robbie Broughton

As La Vuelta a España rolled out yesterday for its 71st edition with a 27.8 km time trial, don’t be fooled into thinking that this Grand Tour is inferior to either the Tour de France or Giro d’Italia. Often relegated to a status as the third best, expect thrills, great bike racing and massive climbs that will test the mettle of the best riders in the world.

The Vuelta shows off Spain's beautiful landscape

Despite being the youngest of the tours, La Vuelta is still a ‘Grand Tour’ with a fascinating history and heritage to rival France’s and Italy’s stories of heroism and romance. It’s produced some wonderful bike racing, rivalries and upsets that began 80 years ago and continue into the modern age of professional cycling.

The first Vuelta was launched in 1935 to boost sales of the Diario Informaciones

It seems incredible to think that anyone would try to establish a Grand Tour race amid the background of political and military turmoil of 1935. Churchill was rallying his fellows Britons for war against Germany, Hitler was building up his military might and Nazi power-base while Franco was establishing himself as Fascist dictator of Spain. Amid this upheaval, like its French and Italian counterparts, it was a newspaper, Juan Pujol’s Diario Informaciones, that launched the first Vuelta in an attempt to boost newspaper sales.

The first races were brutal affairs

It was against all odds that it was even born let alone survived World War II, Civil War and its aftermath of deprivation and an impoverished Europe. The race’s stuttering and uncertain start is reflected by the career of one of its early winners, Julián Berrendero, who lived in exile in France during the Civil War. On returning to his home country in 1939 he became one of an estimated two million people holed up in one of Franco’s prisons along with political dissidents, homosexuals and prostitutes.

He survived for 18 months in various concentration camps having to cope with rampant disease, poor and limited food and being held at the mercy of capricious camp commanders.

Julián Berrendero won five out of the 11 Vueltas he took part in

In an episode reminiscent of Coppi’s incarceration by the British in North Africa, he was standing to attention for a prisoner inspection one day and was picked out and ordered to march to the captain’s office. He was taken by surprise when the captain embraced him: the two had been cyclists before the Civil War and had raced together, but now they were on opposite sides of the country still divided by its fallout.

Berrendero was released in 1941 and the Vuelta was back on the calendar as the Ministry of Education and Leisure attempted to show that life was beginning to return to normal. In the ‘normal’ atmosphere of outlawed divorce, homosexuality and even public kissing, Berendero won that year’s race as well as 1942’s edition where he led from first stage to last. In fact, over 11 years of taking part he won five times in total. Who knows what more he could have achieved if it hadn’t been for his imprisonment?

Like the Tour and the Giro, racing was brutally hard in those days. The Basque rider Máximo Dermit remembered:

“It’s too horrible to imagine. There’s nothing comparable, not even the Alpine stages of the Tour de France; there are moments when it seems like you’re in another world –not a living soul, or a single house for kilometre after kilometre. Just huge, bare rocky mountains. And water! That’s an expensive liquid. In some places, like in Totana, if we asked for water they preferred to give us wine. There was no water to waste on the likes of us.”

Spain’s isolation from the rest of the outside world continued until the early 1950s when it positioned itself as a bulwark against communism and invited American military bases into the country. By 1955, with US petitioning, it had been invited into the UN. The launch of that year’s Vuelta in August, rather than the traditional spring which clashed with the Giro, signalled a rebirth for the fledgling tour. Now riders who would have favoured a trip to Italy for the more established and prestigious race were tempted to Spain. Some sought redemption for disappointing seasons, while other more successful riders could try cement their dominance. And it has remained as such to this day.

The 2016 route

Spain still had to bring itself out of a backward looking culture as it dragged itself into the modern world of the 1980’s after Franco’s death. Laurent Fignon remembered how in the 1983 race:

“It was like the third world…the accommodation and the way we were looked after were not easy to deal with. Sometimes it was barely acceptable. Professional cyclists of today cannot imagine what it was like in the 1980’s in a hotel in the backside of beyond in Asturias or the Pyrenees. The food was rubbish and sometimes there was no hot water, morning or evening.”

Valverde will be keen to win on home soil

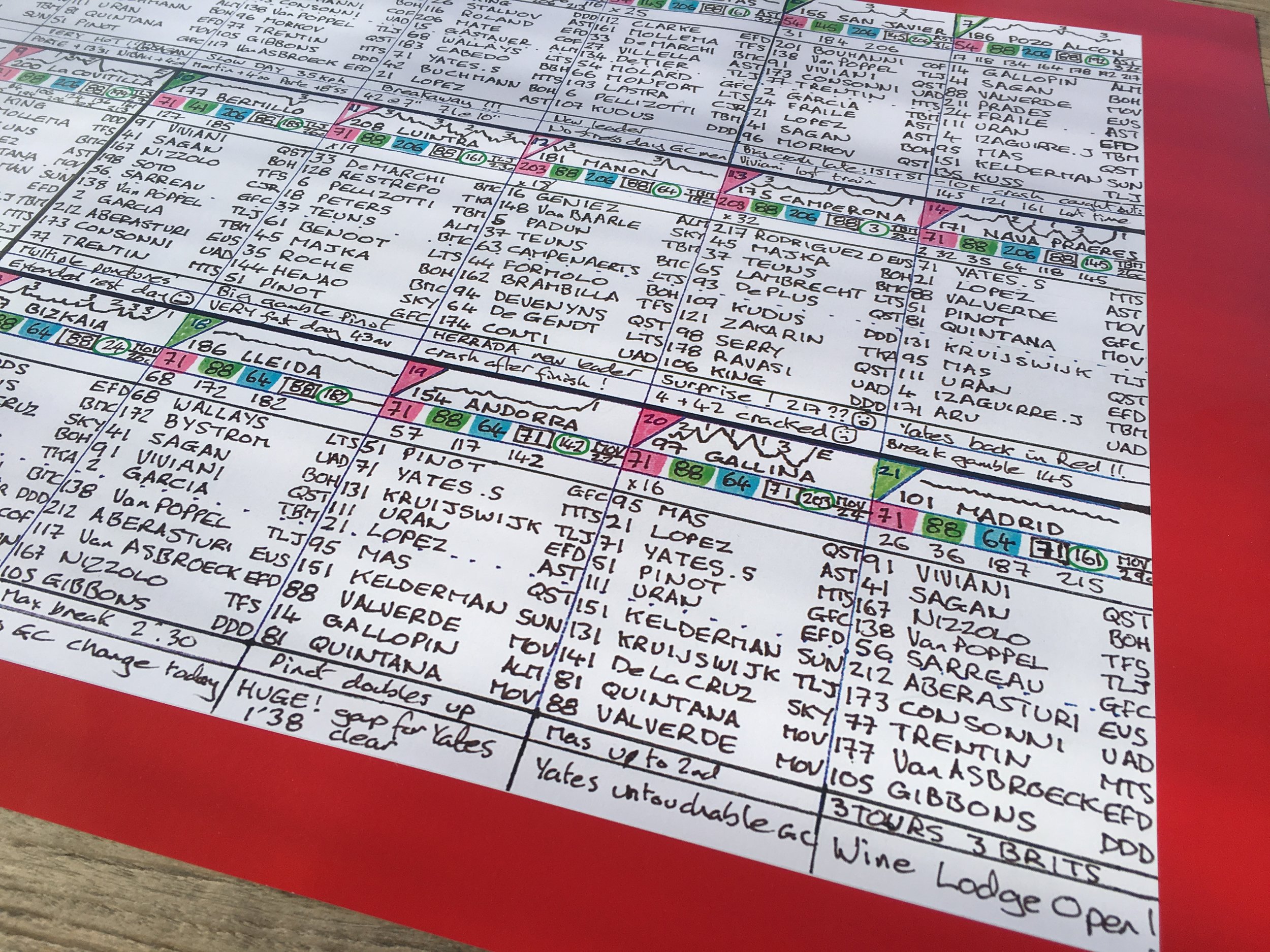

Despite this we have seen some fantastic and dramatic races over the years. La Vuelta is less predictable and harder for strong teams like Team Sky to control compared to the Tour or Giro. Last year eight out of the 21 stages were won by breakaways. There are fewer bunch sprints while the extreme temperatures, uphill finishes and monstrous climbs hark back to the brutal stages of Berrendero’s era.

This year you can also expect a resumption of the Froome/Contador rivalry. As Robert Millar recently pointed out in Cycling Weekly, the Vuelta is a special race for Froome where he has performed well in the past without actually winning. Who can forget the 2012 edition when Froome had to back off to allow the then Team Sky leader, Bradley Wiggins, take the red jersey? He’ll be keen to assert his dominance but will he be able to do so without the extraordinarily talented team he had to back him up in the Tour? Yesterday’s winning performance in the Team Time Trial by Sky will be a foreboding message to the rest of the peloton.

Team Sky won yesterday's Team Time Trial

Contador, of course, is always a favourite here on home territory. He’s won all three of the Vueltas he's competed in, and he’ll want to make amends for his disappointing performance in the Tour last month when he was forced to drop out through injury.

Contador has won all three of the Vueltas he has entered

Will Nairo Quintana show better form? He was lackluster in France, dropped out of the Olympics because of illness and he seems unable to sustain his attacks in the mountains. How will he cope with teammate Valverde, another Spaniard keen to win in front of home fans, vying for top spot in the same team? Then we can throw a few wild cards into the mix: Estaban Chaves looks eager to usurp Quintana’s Colombian crown, Kruijswiejk who’ll want to make up for crashing out of the Giro and off the podium, and Andrew Talansky who looks fresh having not competed in a Grand Tour this year.

Quintana at the front of the peloton

Today sees a relatively flat 159 km route with only a Category 3 climb to contend with from Ourense to Bayonne, one of the few opportunities for the sprinters to make an impact on this year’s Vuelta. Will they be able to reel in the breakaway? As from Monday they’ll be tackling some harder, more hilly rides, by day 6 we’re onto the “mid-mountain” stages and Stage 8 sees the classic La Camperona climb. La Vuelta’s official route description puts it into perspective:

“Its purity, the suffering of the riders and the proximity of the fans all make the Camperona a special place. A truly spectacular stage that, with wind, could be a deciding one.”

The final GC placings could be decided on the penultimate day with a brutal mountain stage from Benidorm to Alto de Aitana which includes a 21km climb with 1,300m of slopes. Finally, the peloton will roll into Madrid on September 11th for a sprint finale and crowning of the overall leader.

Make sure you follow this beautiful Grand Tour. It often throws up drama, the unexpected and fabulous racing. Eurosport will be showing each stage live as well as a highlights programme, while the ITV4 team reunite for their highlights package too.

For more on the history of the Vuelta read Viva La Vuelta! by Lucy Fallon and Adrian Bell