Maggie Dewhurst, a cycle courier from South London, will be going to work this week knowing that she is now entitled to holiday pay, sick pay and the right to a basic national wage. She won her tribunal case against her employer, City Sprint, in what could turn out to be a far-reaching judgement benefiting not just fellow cycle couriers, but other workers in the ‘gig’ economy.

A return of better fortunes for the humble cycle courier?

Cycle couriers have always endured the status of being at the bottom of the pack in the hierarchy. Emily Chappell documented her experiences of the harsh realities of life on the road in her book What Goes Around. Suffering dismissive treatment from office workers and jostling vans and taxis in sometimes dangerous battles on the road has always been part and parcel of the job. But their status with their employers as self-employed meant that they had next to no rights as employees either.

Emily Chappell's What Goes Around told about the harsh life of a cycle courier

If they happened to get injured on the job or simply got sick one day, that meant no wages while they didn’t turn up to work. Even some of the equipment, like their radio, had to be rented off their employer. And if the company decided they didn’t want to employ them any longer, no notice or reason needed to be given. Tax and National Insurance were also put down as the responsibility of the worker not the employer.

As Maggie said in the tribunal, she was classed as an independent contractor in her two years working for City Sprint despite her role being more like a worker. “We spend all day being told what to do, when to do it and how to do it. We’re under their control.”

Tribunal judge Joanna Wade said that because City Sprint had the power to regulate the amount of work available and to limit the size of its fleet, “This gets to the heart of the inequality of bargaining power present in this relationship and shows that this is not a commercial venture between two corporate entities.”

Maggie’s case was supported by the Independent Workers’ Union of Great Britain who said, “This is a huge victory for couriers and workers everywhere who have been asked to sign their rights away for a job.”

Maggie Dewhurst was "delighted" with the judgement

Union vice president Jon Katona went on to say that companies will now have to give their workforce “the rights and protections owed to them according to the true working relationship, or we will come after you.” Meanwhile Maggie said that she was delighted with the tribunal decision.

The lot of the cycle courier has been tough in recent years with less work available as so much business activity can now be transacted electronically, cutting out the need for ‘real’ deliveries of documents. As a result, courier work has been harder to come by.

We could however be seeing a bit of turnaround in the fortunes of the humble cycle courier. The Financial Times recently ran an article about Creative Couriers in North London who are using the cargo bike instead of conventional vans more and more.

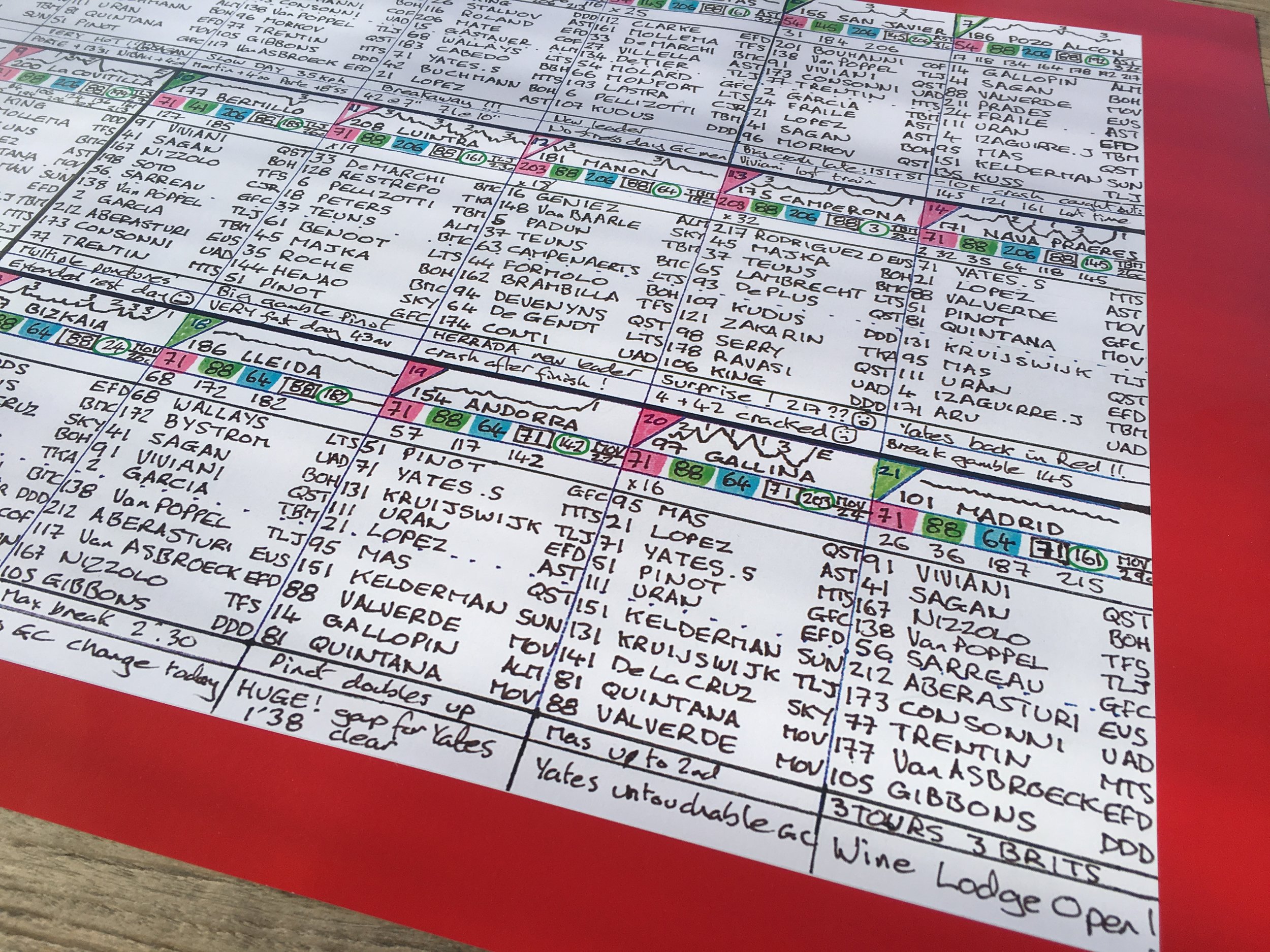

The Bullitt can carry 100kg of cargo

As cycle couriers have switched on to the fact that they can earn more by upgrading from a regular bike to a cargo bike by loading up more deliveries, their employers have begun using them more regularly. They have also found that they can navigate the capital’s congested streets more easily. The average commuter speed by bike in London is 14mph compared to only 8mph by car.

Speaking to the FT, Bill Chidley, a dispatcher at Creative, said that cargo bikes are much cheaper than vans and get through a lot more work. “We would have been tied up for weeks in Christmas work without them.”

DHL use cargo bikes

The Bullitt, designed by Danish bike designers Larry vs Harry, is 2.43 m long and can carry about 100kg of parcels. And there are no problems with parking restrictions on the street. Some of the electrically assisted tricycles meanwhile can take up to 250kg and these are now used by DHL with UPS following close behind with their plans to introduce electrically powered trailers hauled on foot or bike this year.

The message to prospective cycle couriers is: get yourself a load carrying bike and a secure a proper contract with your employer. It could be good times ahead for the humble cycle courier again!